The scramble for climate finance deals ahead of COP26

As countries prepare for what may be the most important United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP) since 2015, the balance of bargaining power between developed and developing countries will have significant implications for the ‘climate justice for development’ agenda.1

On one side, wealthy countries desperately need to redeem credibility having failed to contribute their fair share to emissions reductions commitments and to deliver on pledges of financial support to developing countries. These twin failures have been thrown into a harsher light against the backdrop of uneven COVID-19 recoveries and unequal vaccine access.2,3

On the other, many lower- and middle-income countries are coming to the table with enhanced Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and clearer articulations of their needs related to implementing the Paris Agreement, with early tallies projecting a total of up to US$8.9 trillion by 2030.4,5 However, the finance and investment needed to meet mitigation and adaptation goals will be much larger. The IEA estimates US$1 tn/yr is required for clean energy investment in emerging and low-income economies alone over the next decade.6 This adds urgent and considerable weight to existing demands for wealthy countries to deliver on existing pledges and to set new ambitious goals for long-term predictable climate finance.7,8

South Africa is one country in a firm position to negotiate for financial support to meet its more ambitious NDC target.9,10 A deal to this effect is expected to be announced at the COP, hinging on assistance for an accelerated coal phase-out.11 Any such deal will be of international importance, as it may set the basis for other countries seeking similar support.

Why South Africa, why coal, why now?

South Africa is a prime candidate for a climate finance deal because:

- It’s a crucial site for climate mitigation, as Africa’s biggest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter and 12th largest globally. 55% of energy-related CO2 emissions come from its coal-dominated power sector, another 15% from energy industry own use (mainly coal-to-liquid fuel production).13

- It’s ahead of the curve on climate policy ambition, which has Presidential support (unlike some other countries).14,15 South Africa’s recent actions include: updating its NDC target to an emissions range in 2030 that is broadly consistent with 1.5-2°C warming, committing to net-zero by 2050, and submitting a framework Climate Change Bill to the National Parliament. These commitments are or will be reflected in sector-specific policies.16,17

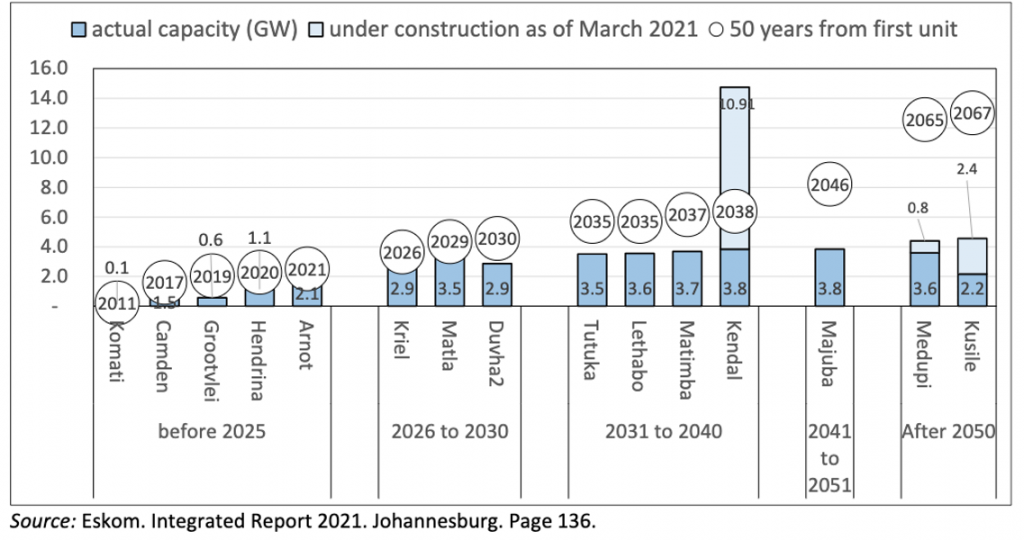

- It’s closer to a transition than many coal-dominant developing country counterparts, such as India or Indonesia. This is partly due to the relatively advanced age of its coal fleet. Though exact dates vary, between 10-12,000 MW of coal capacity is due to be decommissioned before 2030, an additional 7,000 MW by 2035, and the remaining ‘old’ plants by around 2046.18 This leaves Medupi and Kusile (still under construction), each 4,800 MW in size (9,600 MW together). Without early retirement, they will operate into the mid-2060s. South Africa is an important case study for coal phase-out in an emerging economy context.

FIGURE 1: 50-year timelines for existing Eskom coal plants

A complete coal phase-out by 2040 (in line with climate targets) will require significant additional effort to manage the costs and risks of an accelerated coal transition. Such a transition is not inevitable nor will it be easy – climate finance will be an essential lever. South Africa already runs plants beyond ‘factory’ life, like many other countries where plants are operated for more than 60 years, and there are pressing motivations to continue to do so:19,20

- Energy Security: A 15-year supply-side power crisis has resulted in frequent scheduled blackouts to manage constrained supply, with detrimental economic impacts.21 Whether sufficient new capacity can be built to close the supply gap while replacing coal and responding to new demand is uncertain, especially considering that no new power has been successfully procured since 2015.

- Financial Viability of Power Sector: The state-owned power company Eskom is in dire financial and operational crisis, requiring regular state bailouts.22 Around half of the company’s debt is not serviceable from available revenues. Eskom needs to become financially viable for the South African power sector to attract investment (as it is the primary offtaker) and to access loans necessary to invest in its own assets, such as grid infrastructure. This will become harder with an increasing portfolio of stranded assets.

- Employment: South Africa needs to effectively manage job transitions in the coal sector, which directly employs over 90,000 workers, while it also tries to bring down the highest unemployment rate in the world (44.4%, including discouraged workers, in Q2 2021).23

Climate finance for coal phase-out: A square deal

A climate finance deal that supports an accelerated and just South African coal transition, among other climate actions, would benefit all involved. A fair deal would be in the interests of:

- South Africa, to allow for better alignment between climate, social, and development goals, specifically relating to energy security and jobs transitions as part of a just low-carbon transition.

- Wealthier nations, to make good on climate finance commitments and redeem credibility in negotiations – especially for those with absent or underwhelming targets to phase out coal in their own economies. For example: the US has not set a coal phase-out date, while Germany’s 2038 phase-out date is not compatible with fair-share contributions to staying within warming limits. EUR 40bn of public support to power companies, workers, and regional development is included in Germany’s Coal Exit Law, providing a reference point for phase-out costs.24,25

- The broader climate agenda, to provide a pilot case for an accelerated coal transition in an emerging economy context, with the potential to offer lessons for other countries and serve as a model for just climate action.

However, the above win-win-win outcomes will only be achieved if the financial support offered is credible, sufficient, and fit for purpose. Yet, an initial review of reported financing proposals raises questions about how just the transaction will be in reality. The quantity of financial support is a chief concern, as well as how much will be provided on a grant basis and the terms attached to loans.26 On both sides of the equation, transparency will be critical to the legitimacy of the deal and accountability going forward.

Climate finance is an issue that could make or break the COP this year. While a South African deal still hangs in the balance, any announcement will be the canary in the coal mine of the state of negotiations. It remains an important area to watch.

Endnotes

- “Reframing Climate Justice for Development,” Energy for Growth Hub, September 2021.

- https://climateactiontracker.org/

- “Delivering On The $100 Billion Climate Finance Commitment And Transforming Climate Finance,” Independent Expert Group on Climate Finance, UN, December 2020.

- “Executive summary by the Standing Committee on Finance on the first report on the determination of the needs of developing country Parties related to implementing the Convention and the Paris Agreement,” UNFCCC, October 2021.

- According to the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance’s first report on the determination of these needs, noting various methodological limitations and that many needs that have not yet been costed.

- “Financing clean energy transitions in emerging and developing economies,” IEA, 2021.

- “Developing Country Blocs Issue Position Paper ahead of COP 26,” IISD, August 2021.

- “LDCs demand more from developed countries at the COP26,” Chhimi Dema, Kuensel, October 2021.

- “South Africa First Nationally Determined Contribution Under The Paris Agreement,” UNFCCC, September 2021.

- “What Does South Africa’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution Imply For Its Coal Fleet?” Meridian Economics, September 2021.

- “Climate envoys visit South Africa to plan for the end of coal ahead of COP26,” Tunicia Phillips, Mail and Guardian, September 2021.

- “Debt guarantees emerge as a green deal sticky point,” Carol Paton, Business Day, October 2021.

- https://www.climate-transparency.org/

- “From the Desk of the President,” The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- “Mexico was once a climate leader – now it’s betting big on coal,” David Agren, The Guardian, February 2021.

- “South Africa’s Presidential climate commission recommends stronger mitigation target range for updated NDC: close to 1.5°C compatible,” Climate Action Tracker, June 2021.

- “Climate Change Laws of the World,” Grantham Research Institute.

- “Policy Brief for the Presidential Climate Commission: The Just Transition in Coal,” Neva Makgetla, Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies, September 2021.

- “Quantifying operational lifetimes for coal power plants under the Paris goals,” Cui et al., Nature Communications, October 2019.

- “Policy Brief for the Presidential Climate Commission: The Just Transition in Coal,” Neva Makgetla, Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies, September 2021.

- “Power cuts cost South Africa up to $8.3 bln in 2019, research shows,” Reuters, January 2020.

- “The Eskom Crisis: What are we dealing with?” Energy for Growth Hub, August 2019.

- “South Africa’s unemployment rate is now highest in the world,” Prinesha Naidoo, Bloomberg, August 2021.

- “Analysis: Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?” Simon Evans, Carbon Brief, October 2021.

- “Spelling out the coal exit – Germany’s phase-out plan,” Julian Wettengel, Clean Energy Wire, July 2020.

- “Coal phase-out,”Guarav Ganti, Climate Analytics.